As an educational blogger, sometimes there are ideas that rest in your mind and set up camp, refusing to evacuate. This blog post originated from a few weeks ago while doing a coaching session with one of our new language arts teachers and getting on the topic of how to make students more confident in themselves as writers. She was noticing that after a writing minilesson, the same students every day would form a line to get help from her before attempting the writing independently. This was starting to hinder her time with the students in literature study groups she started after the minilesson. Upon further reflection, I noticed the same pattern in my classroom. My students had no trouble reading independently after a reading minilesson, but the reality after a writing minilesson was quite different. Through conversation with my new colleague, the teachers in the writing course I’m currently teaching, and trial and error with my students, I began to create a list of how to take my students from dependent on me to independent, confident writers. The following is a list of all of the tips and tricks I’ve compiled to create writers who are self-starters, problem-solvers, and even ENJOY writing.

1. Get students to own their writing.

By taking time for idea development, students are more likely to find a topic that will hook them in and that they’ll be excited to write about. Never short change this crucial first step of the writing process. As with any part of the writing process, the idea development stage should be explicitly modeled to students. One of my favorite beginning of the year writing activities is to have students do a “rambling autobiography” with an “I love” and “I hate” theme. Students alternate by writing down what they love and what they hate. As you can see from my list below, when you model this concept to students, it’s important to show that great ideas come from descriptive and creative things that they love and hate. What I do with this activity is ask students to go through and identify how items on this list could feed into multiple genres of writing. For instance, if we’re writing a persuasive essay, what items on this list would make for a great persuasive essay? Once you find a topic students are truly passionate about and you give them the freedom to write about that topic, you have already broke down the hardest barrier between writing and your most reluctant writers.

If you’re looking for more pre-writing activities that will help students develop ideas for writing pieces, I’m a huge fan of this applicable book by Linda Reid called 100 Quickwrites.

2. Keep consistent Writing Workshop routines.

I’m such a broken record with this idea of routines across the workshop models. That’s because I’ve been in classrooms with clear routines and expectations and classrooms that do something different every day. I’ve had years in my own teaching where I do a great job of setting up expectations and years where I drop the ball. The difference is so incredibly evident. Do your students and yourself for that matter a favor and decide how Writing Workshop “works” in your classroom. Explicitly teach and model this at the beginning of the school year and stay consistent with those routines and expectations throughout. Below are some questions to consider and think through when developing the routines and expectations for Writing Workshop in your classroom.

-Where are students taking notes during the minilesson? What are students expected to write down?

-Where can students sit and move during independent writing time? How is movement organized? Does the movement allow students to have a more productive writing atmosphere?

-What is the voice volume expectation during independent writing time?

-When do students have a chance to collaborative about their writing with other students?

-How are students supposed to ask you a question about their writing if they have one?

-How do writing conferences work? Do you call the students over for them? Can they sign up for writing conferences as needed?

-How does guided writing work in your classroom?

-What does sharing of writing look like in your classroom?

-What are students supposed to do when they get “stuck” while writing?

*If you’re interested in my “Starting Writing Workshop in Middle School” product that will help you develop these routines and expectations, click here.

3. Model what you’re asking students to do as writers.

Make what goes on in your brain as a writer transparent to students. Whatever you’re asking them to do as writers, you should be trying this out, too. For example, this year I read the book, Killing Mr. Griffin, as an interactive read aloud to my 7th grade students. After we finished the book, I asked them to take a part in the story that wasn’t told and write a “deleted scene.” I wrote a deleted scene of my own, shared my brainstorming of ideas for deleted scenes, and completed the revision and editing process right alongside them as writers. When you try out the writing you’re asking students to do, you’re able to anticipate struggles and stopping points and share those with students during the modeling portion of the minilesson. Also, I’ve found students are much more willing to give writing a shot when they have a model to look at and see that their teacher has given it a try as well. When you’re discussing your writing with students, it’s important to share what helped and what you struggled with. It makes writing real and shows students that in order to achieve something, there will be bumps and struggles. We have to teach students that the first time writing becomes difficult, there are ways to problem solve instead of putting down the pencil and stopping all-together. The best way to do this is to share how we, as their teacher, overcame the same struggles they will face while writing in the same genre. Students will be so much more willing to struggle through writing if they know that’s what writers do. Chapter Two of Jeff Anderson’s book 10 Things Every Writer Needs to Know is titled “Modeling” and gives so many great ideas for how to model writing for students. I highly recommend this book!

4. Problem solve your most reluctant writers.

We all have one or two students in our class who you are already thinking about and you’re saying, “Kasey, these are great tips and all, but you don’t even understand, I have this one student who _________.” Would you believe that I get it? In my class this year, I have one student who it is a constant struggle to get him to engage in anything. I used trial and error this year, and by trial and error, I mean I ended up in constant error. I was beginning to give up hope until one day I was working with this student one-on-one, going around and around with getting him to initiate a writing piece. At this point, I would have been happy with a paragraph, a sentence, to be honest, ANYTHING. I was desperate. That’s when an idea hit me, and I told him to go grab me a laptop. For writing, I sometimes use Google Classroom and have my students turn in their drafts through that platform so that I can give them quick comments and look over what they’ve been working on at anytime. I hopped on Google Classroom right to his draft, and I started typing to him on a Google Doc to prompt him to start writing. He loved that I was prompting him right on his draft, and he began to type. Then I would type another little prompt for him, and he would type some more. This went on and on for over a half and hour and a through a full page of typing. My heart was absolutely overjoyed, and I had legitimate tears in my eyes. The best part of the whole thing though? He was so proud of what HE had accomplished as a writer. After struggling through weeks at the beginning of the school year with getting him to write, he now will try any writing assignment if I hop on a Google Doc with him and give him one or two little writing prompt nudges. What’s funny is it seems like each writing assignment he relies on me less and less. Below is a screen shot of his first “breakthrough” piece with my prompts in pink. My point of this story is to NEVER GIVE UP on your most reluctant writers and just keep trying until something works.

5. Build in intentional writing collaboration between students during the have-a-go and share.

Writing is a collaborative process. Students who are able to voice their ideas and get excited about them will take more ownership in their writing. Additionally, being able to orally talk about ideas and how those ideas will translate into writing will help writers with what to say so that the actual act of writing down those ideas is easier. During different portions of the minilesson students need to know what is expected of them. If they know there will be time to voice ideas and collaborate with their peers, it will be easier for them to remain silent in the parts of the minilesson where silence is needed as much as the collaboration is needed during other parts.

Minilesson Statement/Author’s Talk: Silence while the teacher explains today’s objective.

Modeling: Silence while the teaching is modeling the concept and participation when asked for by the teacher.

Have-a-go: Student collaboration as they are asked to complete a task that will scaffold the minilesson prior to students taking on the concept independently.

Application: SILENCE. Writers need a quiet space to concentrate and write. The teacher may be holding writing conferences or a guided reading group in part of the classroom, but this is the only talking that is happening.

Share: This is the chance for students to share and ask questions about the work they’ve done as writers today.

6. Have students collect and categorize “writing gems.”

Connect the reading and writing processes by having students read through the lens of writers. If students view the authors of their independent reading books as writing mentors, they can view the authors as models to strive for in their own writing. Have students pretend they are on a scavenger hunt while reading, and if they happen to come across something the writer does that strikes them, don’t just read over it and forget its beauty, take the time to jot down that idea to reference later when coming up with ideas for their own writing. Students can keep writing gem lists in their Writer’s Notebooks on topics such as: dialogue tags, ways to describe characters’ appearances, ways to describe setting, transitions, figurative language, etc. The writing gem lists can be on any topic, and they come in handy when students get “stuck” in their writing or can’t think of how to make their writing better during the revision process. I got the idea of having my students keep lists of writing gems in Chapter Three of Jeff Anderson’s book, Mechanically Inclined. This idea, along with so many others contained in this book, has been instrumental in helping me form Writing Workshop in my middle school classroom.

7. Assess writing as a constant continuum.

Every writer in your classroom has places he or she can improve and places he or she did well in each piece of writing. As teachers, it’s our job to lift and progress our students as writers. When I give feedback to my students, I try to write at least one specific thing the student did well as a writer and one specific thing the student could do to make his/her writing better. Students need both and should feel confident in their identity as writers while also knowing that there are always places writers can grow.

8. Don’t fix everything in writing conferences. (Have students pick one line of thinking)

If students know that they can come to you for a writing conference at any time and you will “fix” all of their errors and tell them what to improve, why would they ever engage in revision on their own? When a student comes to me for a writing conference, I ask that he/she comes to the conference with a clear focus of what he/she would like feedback on. As I’m reading over a student’s writing, I may also see something I want to bring up to the student. However, I may also see ten things I want to bring up with the student. It’s times like these where I need to ask myself how I’m going to make the biggest difference. Hypothetically speaking, do I want to teach the student how to fish or give him/her fish to eat? Yes, I could easily fix everything to make that one piece of writing perfect, but am I doing this student any favors when he/she goes to write the next piece of writing? I would rather my students learn something as writers that they will transfer into the current piece of writing and future pieces of writing. The next time around, we’ll focus our line of thinking on something else. The best book I’ve ever read on writing conferences is Carl Anderson’s How’s It Going?, a must read for any teacher who wants to make writing conferences count.

9. Create contagious writing energy through energetic silence.

Think back to college when you were in the library and everyone around you was intently studying and typing essays. Even though it was silent, you were still able to feed off of the energy of others because them working hard inspired you to work hard. I try to re-create this same effect in my classroom. If everyone is working hard as writers during independent writing time, it’s a domino effect of contagious energy without anyone uttering a word.

10. Accept that students’ writing will look different from one another.

The advanced students in your class shouldn’t have limits placed on their writing. If you are expecting everyone to turn in a similar piece of writing, you are putting a ceiling on writing that might have included something you didn’t even consider. On the flip side, the only way you’re going to get the writing of students who struggle significantly to look the same as the perfect picture in your mind is if you “revise” their writing for them until it looks the way YOU want it to look. Writing is a continuum of learning, and your students are going to fall in different places on that continuum. I would rather see where students are at independently so that I know what to do to challenge and support them next.

11. Teach students to use mentor texts as resources to mimic.

If you’re having students write in a specific genre, it’s helpful to have a “staple” mentor text that you’re using throughout the writing process. The students will get to know this mentor text, and you won’t have to waste time reading different mentor texts each day. I find many of the questions I get from students during independent writing time can be answered through the mentor text. For example, if a student asked, “How should I start my fiction story?” my response could be, “It looks like the author of this fiction story began with dialogue between two of the characters. What do you think about that idea?” Students love when they can see a mentor text that gives them tangible ideas of things they could try in their own writing. For me in my classroom, most of my mentor texts are samples of my own writing. Below is an example of my “deleted scene” from the book Killing Mr. Griffin that I used as a mentor text while my students were writing their deleted scenes.

12. Have a way students can ask you questions when you’re busy with other students.

Students must learn quickly in Writing Workshop that I am not available at the drop of a hat. When I’m in a writing conference or a guided writing group, the only time I would expect to be interrupted by another student is in the case of an emergency. I do acknowledge though that a student may have a burning question. A new technique I’ve implemented this school year is having students write their questions down on a sticky note and leaving them silently with me at the small group table. I can then decide if it’s a question I should address quickly in between writing conferences or something I can answer at the end of the class period. Having students write their questions on a Post-it note also encourages students to question whether or not the question is worth asking at all. We all know a few students who need a little practice at that. 🙂

13. Work intentionally to build students’ confidence, stamina, and self-initiation for writing.

These three areas are the keys to creating independent writers in your classroom. One of my favorite ways to do this is an idea from Jeff Anderson’s book, 10 Things Every Writer Should Know called “Power Writing.” This is a great routine to start at the beginning of the year where you would write two different words on the board and give students a short time frame (start with one minute) to write as much as they can about whatever comes to mind because of one of the words. Have students count up how many words they’ve written and work to improve their word count as the year goes on.

14. Watch your language.

Pay close attention to what you say to your students when it’s time for them to begin independent writing. My favorite “send-off” line is “do your best writing today.” I’m not telling them that their writing has to look identical to mine or it’s unacceptable, but I’m also not telling them to just freely write whatever they want and forget about all those things they know how to do as writers. I’m simply asking them to do their best, which holds high expectations without over intimidating our student writers.

15. Focus on conventions without letting conventions be the only focus. (Express Lane Edits)

Remember the SIX Traits of Writing? Ideas, Sentence Fluency, Organization, Voice, Word Choice, and Conventions. There are six traits because each trait is pivotal to having effective writing. I truly think some people believe proper grammar will automatically equal phenomenal writing. The effect is sometimes our students gets so freaked out that their not “doing it right” that they completely lose control over the other five traits while focusing only on conventions. I would rather my students get a lot of ideas down and get creative with their word choice and infuse voice that have everything perfect.

Please hear me here. I do value conventions. Horrible conventions can erase a strong voice or a great idea because the reader is so focused on the disastrous spelling or the run-on sentences. One way that I love to combat this is through the use of Express Lane Edits, another hack from Jeff Anderson. At the end of a writing period, I ask students to look through their current draft using one lens. For instance, I may ask them to read over their draft and evaluate their use of commas. Each day, I can incorporate an informal Express Lane Edit while students are drafting and revising. This is the perfect way to keep the focus a focus on conventions while keeping the other traits alive, too.

16. Get students to please themselves as writers, not you.

This tip is crystal clear, and when you ask yourself who your students are trying to please and notice their behaviors during independent writing, you will know the answer right away. The more we can shift away from our students writing to please us to our students writing to please themselves, the more independent our writers will become.

17. Make sure the minilessons you use have a clear focus.

If during a class period you’re finding many of your students are unclear about how they’re supposed to apply the minilesson to their independent writing, ask yourself how clear the minilesson was. Maybe it was way too broad of a minilesson and you’re asking students to do ten things at once to their writing, or maybe your modeling was confusing. Whatever the case may be, sometimes we have to take responsibility for students not being independent in their writing because we’re not being clear in our teaching.

18. Support writing instruction through other contexts.

Why not study how writers use dialogue conventions through Sentence Stalking when your class is writing fiction stories and you know they’ll be incorporating a ton of dialogue?

If your having students write a memoir, why not read a memoir during Interactive Read Aloud?

If we’re using a true Balanced Literacy framework, all aspects of literacy should connect together. We can make our student writers more independent by strategically embedding content that will help them as writers through other contexts.

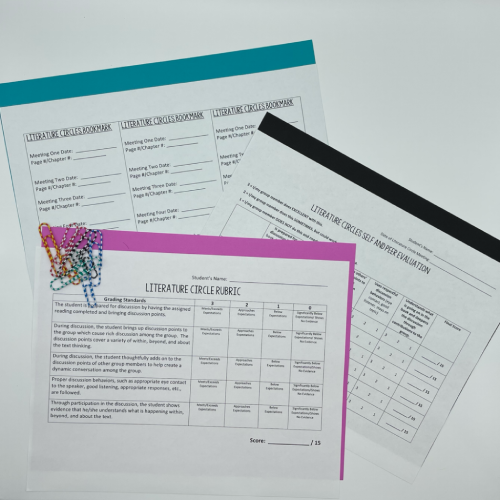

19. Take time for self-reflection of writing behaviors.

Ask students to answer writing self-reflection questions independently, respond in writing, talk them over with a partner or a small group, discuss them as a class, hold up their fingers on a scale of 1-5, etc. to self-evaluate their writing behaviors for the day, etc. Asking students questions such as the ones listed below on a consistent basis will help students take responsibility for their writing through the behaviors their exhibiting in class.

-Was I a self-initiator of my writing today within the first two minutes of independent writing time?

-Did I help to make quiet, contagious, positive writing energy in the classroom today?

-Did I get stationed right away and focus on my own writing without interrupting the writing of others?

-Did I write the entire time, only taking breaks to think of new ideas?

20. Have different writing contexts throughout the year.

Writing should not always be done in the same way. Think of your life and the different contexts you are expected to perform in as a writer across a week’s time period. We should mimic this same effect for our students to teach them that writing is done for a variety of purposes.

-Different genres

-Variety of time contexts (day, two-day, week, 3-4 weeks)

-Writing Process Variation (emphasis should be placed on different pieces of the writing process for different pieces of writing)

-Choice vs. No Choice (sometimes writing is done for a prompt, sometimes writing is completely a free choice, sometimes there is choice within a genres, etc.)

-Different audiences

-Different levels of formality

-Different technologies

Well, there you have it! Twenty ways to get your students to become the writers you have always dreamed they would become through finding their independence and seeing themselves as a real writer with authentic ideas and important things to say.