For middle school ELA teachers, the grading struggle is real. We want to be able to provide meaningful feedback to students on their reading and writing daily, but it isn’t feasible to do this with 50, 75, 100, or 125 students. (Yes, I hear from middle school ELA teachers who have upwards of 125 students that they see daily!) Your relationship with giving feedback to students probably falls into one of the categories below.

A. Teachers assign meaningful reading/writing tasks daily, but never give any feedback. In turn, students get used to not getting feedback, and they let the quality of their work drop.

B. Teachers assign meaningful reading/writing tasks daily and completely burn themselves out attempting to give daily feedback to students. They neglect themselves and their families in an attempt to provide feedback to 50+ students on a daily basis. This just isn’t sustainable.

C. Teachers avoid assigning meaningful reading/writing tasks all together because they know they won’t have time to give feedback. In this scenario, it’s easier to just avoid giving having the option of giving feedback altogether.

We have all been in each of the scenarios above, and none of them are fun or feel good. This is a topic that I get pretty passionate about because I believe middle school ELA teachers should be able to have a life, and that middle school students should have meaningful reading and writing tasks with intentional feedback daily. So how do we get both? I have found success with a variety of the strategies below, and I think you will, too!

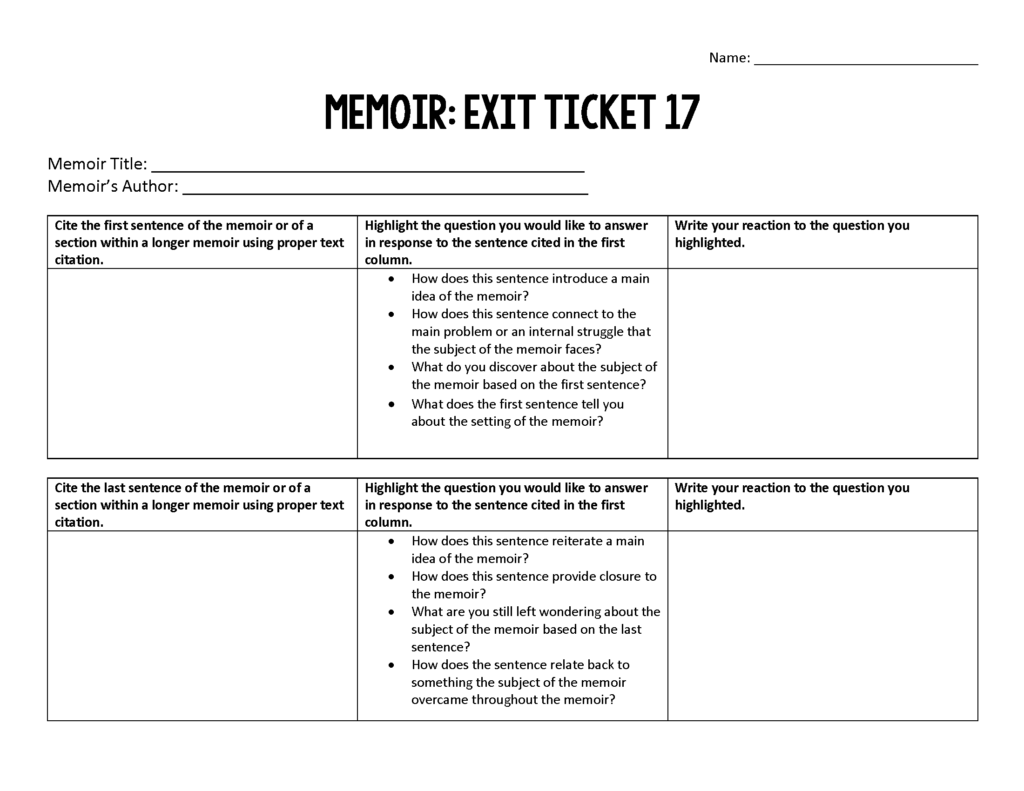

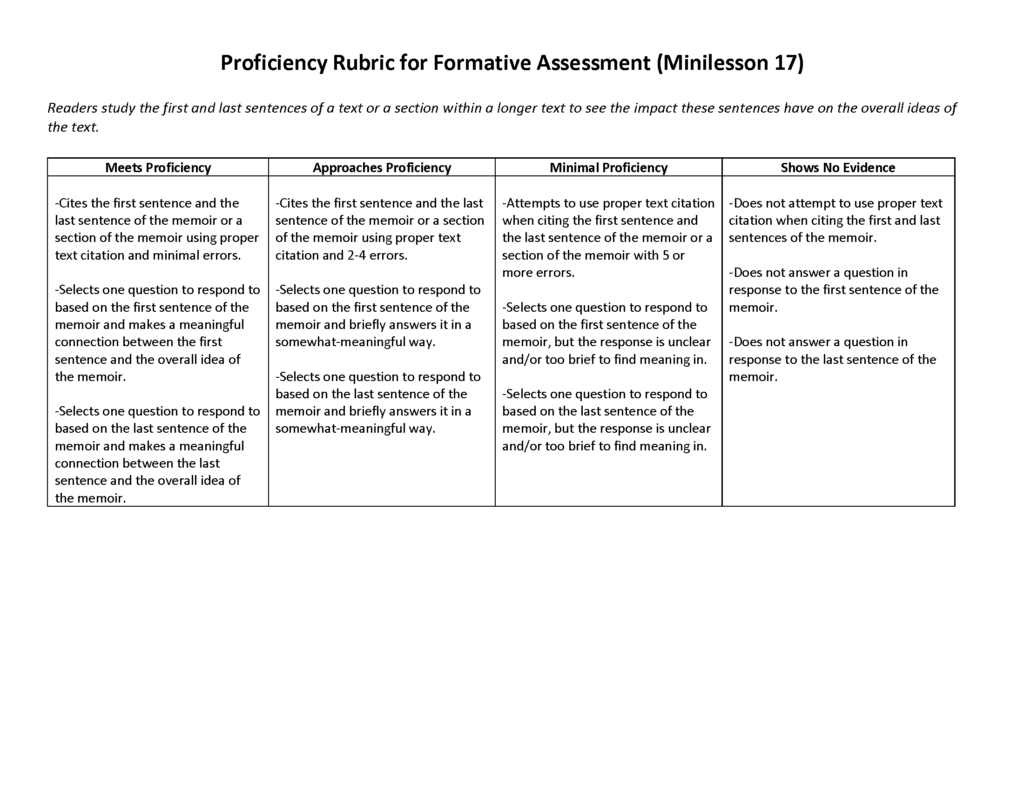

The first step to the strategies below working is to develop a detailed proficiency rubric for the work you are asking students to do as readers and writers. Creating proficiency rubrics for each task you ask students to do can feel tedious and be a pain, but the creation of these rubrics serves multiple purposes. The first purpose is to allow the teacher to define what it means to meet proficiency, approach proficiency, have minimal proficiency, or show no evidence for each formative assessment. The second purpose is that it’s a great tool for communicating expectations for an assignment to students. The third purpose is that proficiency rubrics are perfect for teams of teachers who work in a PLC model and want to have common formative assessments. The PLC question of, “How will we know if they learned it?” is answered much easier with common proficiency rubrics. Discussion about how to respond to students who are showing minimal proficiency and students who are exceeding proficiency are much easier to have, too. Below is an example of a formative assessment I use in my Memoir Reading Unit along with its coordinating proficiency rubric.

- Feedback to Five: Take the last five minutes of class and check-in with five students for one minute each. During the minute you spend with each student, look over the work they did as a reader or writer that day and try to give them really focused feedback based on the proficiency rubric. If the student is really off-base, try to avoid trying to do a one minute correct-all. Keep the feedback conversational and focused, so that students feel lifted by the conversation and take away something they could apply to their reading or writing in the future. If the student’s work is high quality, still go beyond “great job” and give them really specific positive feedback and ask a question that may challenge their thinking and continue to lift their learning for the day. Try this strategy for one week, and across the week, you should be able to check-in with each student one time if you have class sizes of around 25. If your class sizes are larger or smaller, you can adjust how many students to check-in with daily. What I love about this strategy is that there is zero grading time outside of class for the teacher, and there is arguably no better way to provide feedback than one-one-one, face-to-face with students.

- Partner/Small Group Feedback: Newsflash: YOU AS THE TEACHER DO NOT ALWAYS HAVE TO BE THE PROVIDER OF FEEDBACK! In fact, sometimes students take feedback better from their peers than they do their teacher. The beauty of having a detailed proficiency rubric (like the rubric pictured above) is that students can use the specific criteria listed to give focused, honest feedback to a peer in a partner or small group setting. A few ideas for how you could do this:

-Have students exchange their work with one another and rate each other using the proficiency rubric. After they have circled where they think their peer’s work stands on the proficiency rubric, encourage students to get back together with one another and give each other feedback on what they did well and improvements they could make.

-Ask students to read a specific part of their work aloud to one another and give verbal feedback on one focused area of the proficiency rubric.

-Have students “share” their Google Doc/Form/Slides with one another and then use “comments” to give feedback to each other electronically.

Once again, a major pro to this method of feedback is there is no additional time outside of class needed for the teacher to give. If the formative assessment was something you wanted to record in your grade book, you could ask students to turn it in and then quickly look through to see if the scores given were accurate or needed adjustments. If the purpose of the formative assessment was to give feedback, however, the peer feedback in this circumstance should be sufficient. - Self-Assessment (with guided teacher feedback): If you have ever used self-assessment with students, you know that most students are accurate with where they would rate themselves on a rubric. Some are even harder on themselves than I would be when grading. For this method, use the last five minutes of class time and ask students to rate themselves using the proficiency rubric you created for that formative assessment. Take it a step further by giving guided teacher feedback as students are rating themselves on the proficiency rubric. Here are some examples of language you could use:

-“Let’s look at the first piece of criteria on the proficiency rubric. Please give yourself “Meets Proficiency” for this criteria if…”

-“If you are in the “Approaches Proficiency” category for this piece of criteria. One way you can improve your work is to…”

-“After self-assessing your exit ticket today, if you’re ready to submit your best work you can turn it in now. If there is something you want to improve, feel free to turn in your exit ticket at the beginning of class tomorrow.”

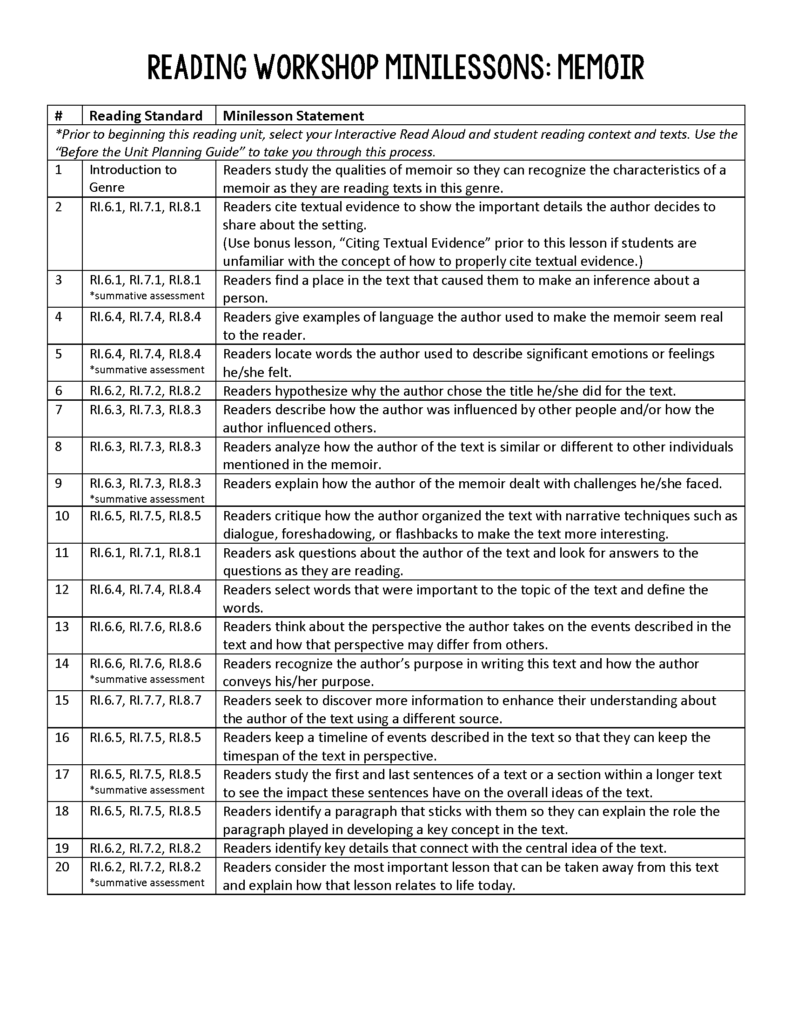

Once again, this feedback method involves zero teacher time outside of class, and students are still getting direct verbal feedback from you on the work they did that day. As mentioned in the peer feedback strategy above, if you did want to enter this formative assessment into the grade book, you could collect the formative assessment and look through how students self-assessed themselves and make adjustments as needed. - Save Teacher Feedback for What’s Most Important: While I do believe it’s important to have some sort of formative assessment daily, I do not think it’s necessary for teachers to personally give feedback on every single formative assessment. This blog post is all about ideas of ways to give feedback without burning yourself out. This blog post is not saying that teachers should never give feedback to students. There is a time and a place for teacher feedback. Teachers should be intentional about when this is though. For me, I use unit plans to know when I am going to take the time to provide student feedback on their formative assessments. At the end of each reading unit, I give a summative assessment. The summative assessment is based off of the six priority reading standards I grade on for ELA. Even though I cover each priority reading standard at least 3 times across the reading unit, only one of the reading minilessons and its coordinating formative assessment will make its way to the summative assessment. It is my goal for students to get high quality feedback from me on the formative assessments that will be on the summative assessment. For a breakdown on how I use Standards Based Grading in ELA for reading, check out my YouTube video where I go into specifics here. Below is the reading unit plan for my Memoir Reading Unit. You will notice that six reading minilessons are marked “summative assessment,” one for each of the priority reading standards. These are the formative assessments I would give teacher feedback on.

5. Share a Student Example: This feedback method is gold because it’s simple and effective. At the end of class with a few minutes remaining, ask if there is a student who is willing to let you assess their formative assessment in front of the whole class. Put the student’s formative assessment under a document camera, read their work aloud, and then grade the student using the proficiency rubric. Be explicit about why you are circling the proficiency level you are on the rubric. If this process goes quick, ask if there is another student volunteer and repeat. When you’re done, tell students, “Turn your formative assessment in if you’re ready. If you have some things you want to adjust, feel free to turn your formative assessment in before class tomorrow.”

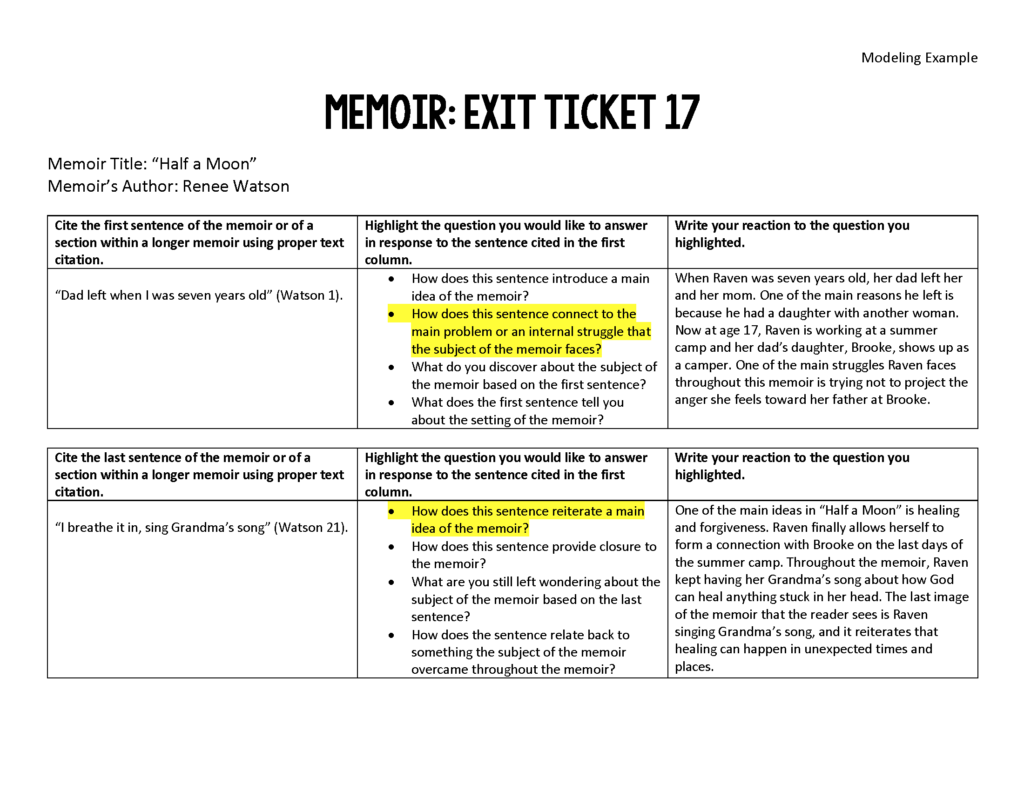

6. Model an Example: Sometimes we give students a formative assessment, read the directions, tell them what to do, and have them go for it. Sharing a modeled example of what you’re actually asking students to do is so helpful. Sometimes what is so obvious to us is not quite as obvious to most of our students. We lose perspective that they’re traveling from class-to-class and have a lot of other things on their minds. Explicit clarity is needed for middle school students’ brains. Let’s be real: it’s needed even more for adult brains. If I can see an example, I am much more likely to understand and to try to do whatever the task is. If you’re doing a read aloud in your reading unit, using the read aloud to do an example on the formative assessment in front of students is a highly effective way of modeling. At the end of class, bring the modeled example back up in relation to the proficiency rubric as students think about their work.

I would recommend using a variety of the feedback strategies above across the school year. You might find one that feels natural or works really well for your students. Like anything though, variety is the spice of life. Keep students engaged through mixing up feedback methods. Consistently giving feedback will keep students tuned into their work and putting in their best effort. Giving consistent, specific feedback also will affect students’ learning growth. I hope these ideas were helpful and reduce the stress and workload that comes with trying to give feedback daily.

If you loved the idea of having reading units with:

-A reading unit plan

-20 unique reading minilessons specific to the genre of the reading unit

-Daily formative assessments with coordinating proficiency rubrics

-Modeling examples for each formative assessment

-A summative assessment

then you should definitely check out my reading units for middle school. There are seven units total that are designed to make up a year’s worth of middle school reading instruction. I’ll link them below for your reference.

Realistic Fiction Reading Unit

Historical Fiction Reading Unit

Science Fiction/Fantasy Reading Unit

Expository Nonfiction Reading Unit

Memoir Reading Unit

Reading Unit Growing Bundle

Thanks so much for reading this blog post!

Kasey